Глава 1 Глава 2 Глава 3 Глава 4 Глава 5 Глава 6 Глава 7 Послесловие

Литература Summaries Приложения

SUMMARY

The Pitch Nature of Primitive Singing

Sovetsky Kompozitor Publications, Moscow, 1986

0.1. To explore the mechanisms of archaic melopoeia, one must find an unbiased approach, free from many an academic prejudice. The point is that what is known as mature tonality should be regarded merely as one of the multifarious forms of thinking in terms of pitch—not as the norm; otherwise we shall have to qualify primordial melodies as anomalous and, what is more, nonsensical. To put it differently, we are in need of a methodology which would allow for both the well-worked-out systems of organization of the sound substance and those underlying all the manifold phenomena of early folk-music.

0.2. In selecting and classifying the material for study, we should never draw exclusively on aesthetic criteria, for they turn out to be restrictive with respect to a wide range of observable phenomena. Likewise, neither the notions of simplicity and complexity nor the concepts of progress and regress can be considered relevant to the forms of tonal organization intrinsic to the archaic layers of musical folklore.

0.3. Strictly speaking, the main-springs of the development of tonal systems ought to be researched into from a pronouncedly historical angle, with the structural essentials of particular phenomena being examined in terms of their genesis. But since the evolution of music of oral tradition is virtually untraceable on the plane of historicity, nothing else is left than to go the path of logical construction.

0.4. Initial forms of organization of tones grew up mainly in the bosom of primitive singing, whereas the instrumental culture was, as it were, secondary in this respect until a certain stage in evolution1; when we speak of singing here we mean predominantly solo inflection, with the practice of singing together affecting the physiognomy of melody and its formative forces as a strong corrective factor. The uniformity of acoustic and physiologic conditions, of generating and perceiving the vocal sound determines the universality of logical norms of operating the tone-material.

0.5. The pitch aspect of early folk singing is syncretically bound up with all the other sides of a melodic whole—metre, rhythm architectonics, dynamics, articulation, phrasing, gesticulation and, notably, timbre, which often comes to the fore and, what is more, proves to be the principal vehicle of the meaning of many a primitive musical utterance.

0.6. In view of these circumstances, transcribing (writing down) early folk melodies appears rather a problematic undertaking. Firmly associated, by its very origin, with the idea of European tonality, the five-line notation is far from being conducive to an adequate comprehension of the initial norms of melodic consciousness. Nevertheless it remains, in many respects, an irreplaceable instrument of analysing the melodic material under consideration in terms of pitch, and needs, in this capacity, further improvement, in particular by dint of introducing into the system of music-writing a temperament based on a subdivision of the semitone, which would make for the formalization and operationalization of pitch-dimensional analysis2.

0.7. To scrutinize the foundations of archaic melodies, we should preliminarily work out a general systematization of their types, albeit partly by way of intuitive construction, so as to realize that the evolution of primeval melody must have been 'a system as a process', with definite primordial principles of melodization each displaying different expressive potentialities and being, at the very outset, capable of embarking on the path of interaction and reciprocation. A residual effect of those principles may be traced even to the highly developed forms of modern music, which often deliberately turns back to the very sources of thinking in terms of melody.

0.8. The historical accumulation of means of expression, making up a multilaminate 'counterpoint' in every present-day song style, enables us to use virtually any song melody (looked at, as a matter of course, from a definite angle) as a source of information on what can be described as initial principles of organization of tones, but the most appropriate material can be found in children's folklore, in the strains spontaneously produced by grown-ups and in evidently wrong singing.

0.9. A problem per se is the matter of working out a correct terminology and defining the relevant fundamental notions. Here cross-analogies may be useful, with terms borrowed from different fields of knowledge by way of comparison, specification and amendment. Such a subsidiary device, along with the growing reliability of notations owing to the elaboration of new methods of visual presentation of sounds, gives rise to certain premises for the algorhythmization of pitch-orientated analysis and the computerized verification of hypotheses concerning the origin and evolution of tonal systems.

1.0. It ought to be emphasized that the formation of stable tone-complexes capable of musical expression is a triune process characterized by:

a) definite stages ('conceptions') of a melody tone coming forth (plane of intonation, I);

b) a certain type of intertonal (functional) relations being formed (functional plane, F);

c) scales taking shape and being gradually stabilized (scalar plane, S).

Logically, the stage of maturity of tonal organization must have been preceded by a phase of relative disorder of pitch-levels applied within a melody, with no fixed scales, no distinct intertonal relations and, actually, no definite tones, the latter factor determining, as a matter of course, both the character of interrelations of pitch-levels and the nature of the 'scalar projection' of those interrelations.

The relevant melodic material gives evidence of existence of at least three general principles of employing different pitch-levels in early vocal melody-making, which will be denoted here by the three initial letters of the Greek alphabet.

1.1. The α-principle implies operating what may be described as unstratified registers, which results in sounds without clearly distinguishable pitch. Such kind of singing, which may be qualified as singing based on contrasting registers, is characterized by the prevalence of timbre, which absorbs (and, as it were, dissolves in itself) the pitch quality of sounds so that pitch proper is not yet relevant to the sense of musical speech. In transcribing a melody of this type in terms of our five-line notation we virtually misinterprete the musical reality, representing what has no direct connection with the pitch by means of pitch symbols. Most striking examples of that are wide-ambitus extatic lamentations (see Ex. 1, 2, 6).

1.2. The β-principle implies operating distinct pitch-levels which are, however, constantly changing — mostly sliding down. Here, too, notations usually appear to be inadequate. We come across such cases in various calls as well as where special stress is laid on the articulation of words (see Ex. 91 and 18).

1.3. The γ-principle implies operating a number of degrees (melody tones) within one and the same vocal register, and — better than the two principles described above — corresponds with our ideas of definite pitch-levels as the tone-material of singing; yet, in contrast with melody-making in terms of crystallized tonality, the γ-degrees are subject to considerable, though gradual, changes in respect of pitch when a melodic unit is repeated, so that different versions of a tone may be integrated into one transformative degree. Such singing, unstable in pitch due to the employment of mobile degrees, or, in other words, singing without fixed scales, appears to have been the immediate forerunner ,of singing in the context of mature tonality, and is to be found in various song genres (see Ex. 36 and 37).

1.4. The three general principles of operating the pitch categories in archaic singing can be realized independently of one another — in three separate classes of early folk melodies. One cannot exclude the possibility that other principles will be uncovered, say, a δ-principle. But — even if there are only three of them — in classifying instances of early folk melopoeia we have to do with a wide range of real forms of dealing with the pitch material, for our three principles can take effect in different combinations — alternating with one another or interacting within one and the same tune, so besides the three 'pure' classes of archaic melodization there are four 'mixed' classes: αβ (Ex. 26), γβ (Ex. 21), γα (Ex.5 and 93) and αβγ (Ex 39, 28, 25). In any case, the coexistence of different vocal registers in a tune can be regarded as a manifestation of the α-principle; the descending physiognomy of the melodic contour and the use of gliding inflection, as an effect of the β-principle; and the employment of different versions (pitch-levels) of essentially the same degrees (melody tones), as an indication of the γ-principle.

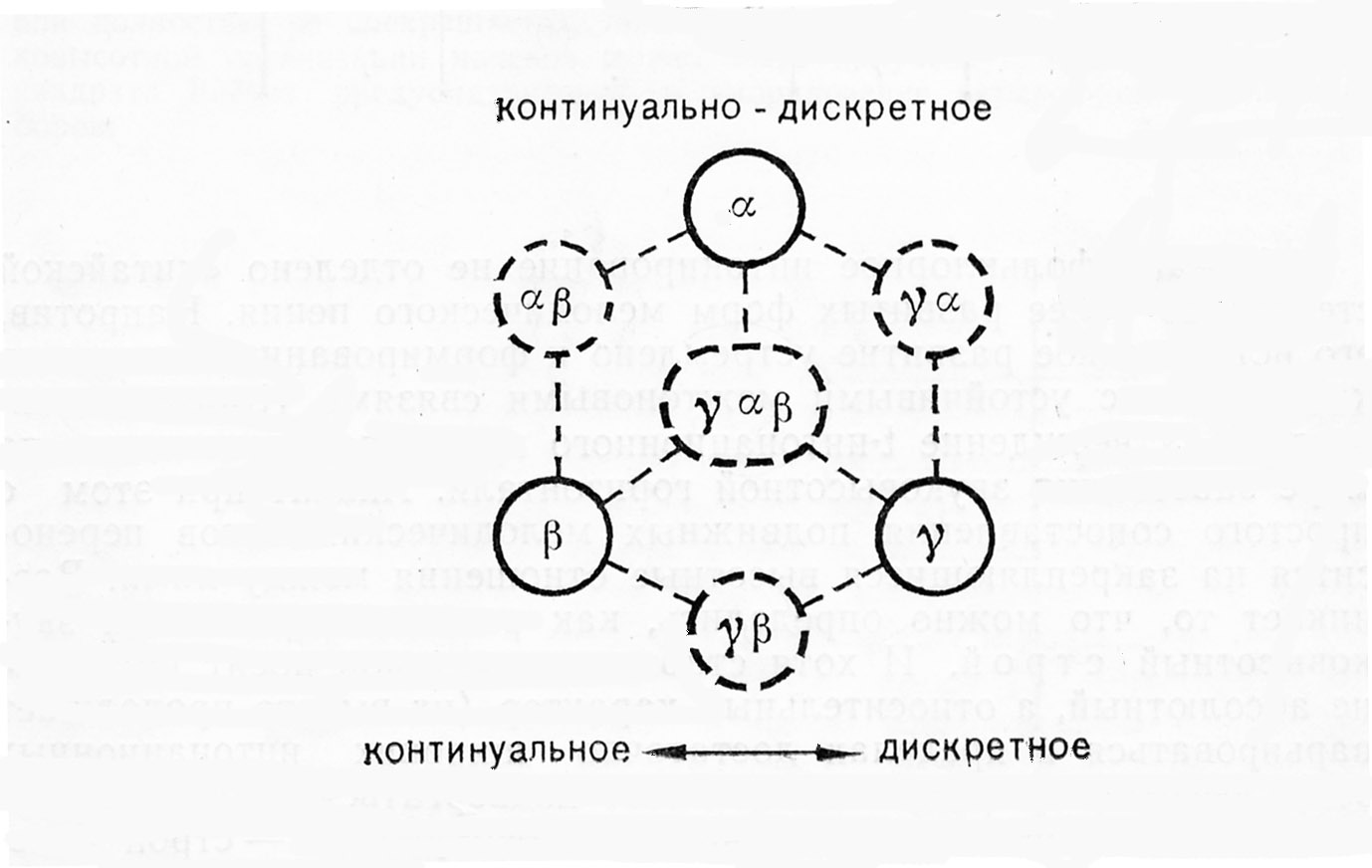

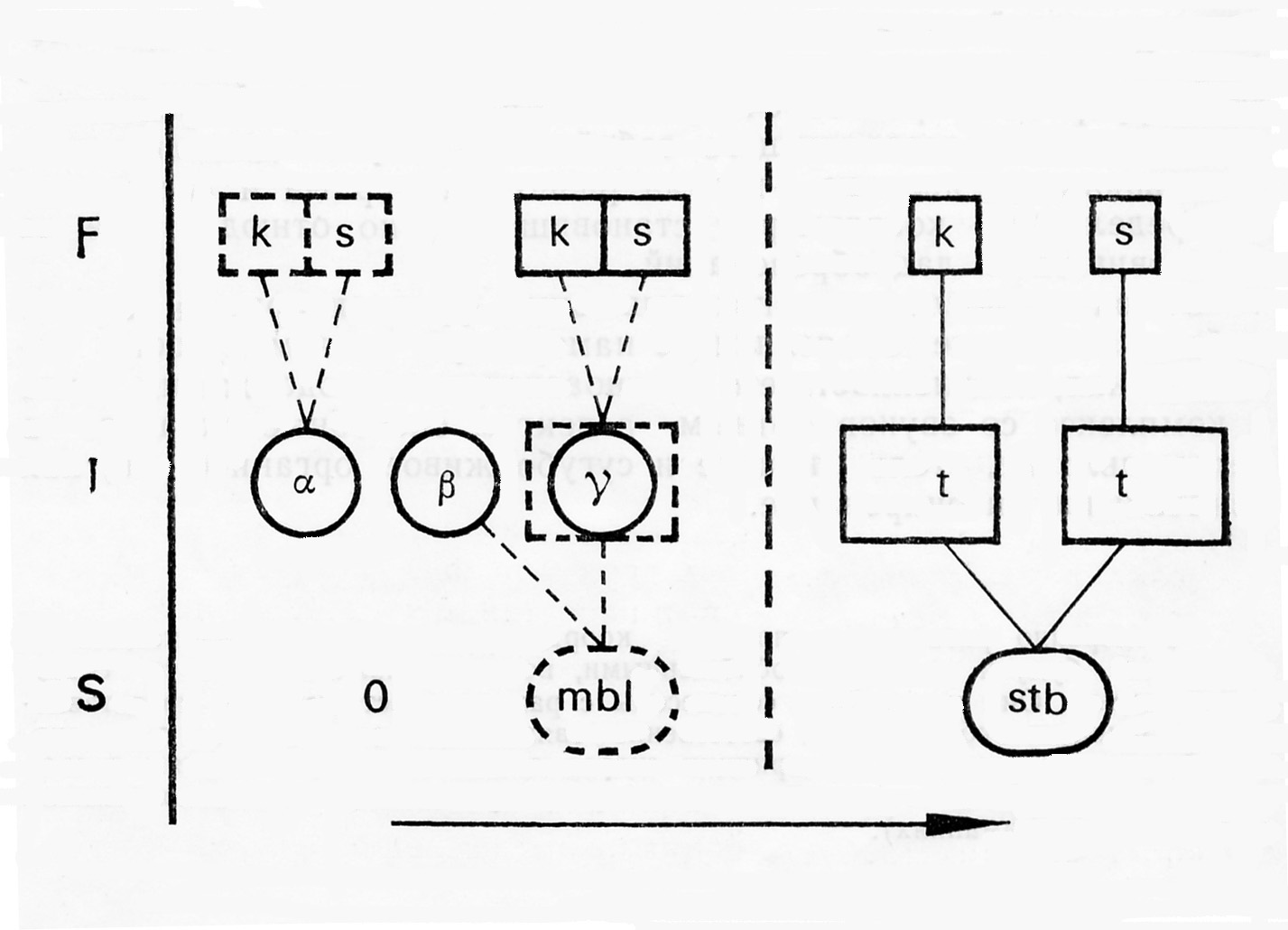

The interrelation of the above-mentioned classes as connected with the interplay of continuity and discreteness in the pitch structure of early folk melody is presented in the diagram 1:

Diagram 1

1.5. The classification put forward in 1.1-1.4. admits of introducing quantitative characteristics and constructing a hierarchy of types of melody in accordance with their expressive potentialities — from the β-class, extremely continuous, up to the γ-category, which is the most discrete among the types of singing in terms of mobile scales, with the α-division (continuous in respect of tones and discrete as regards the registers) ranking in between.

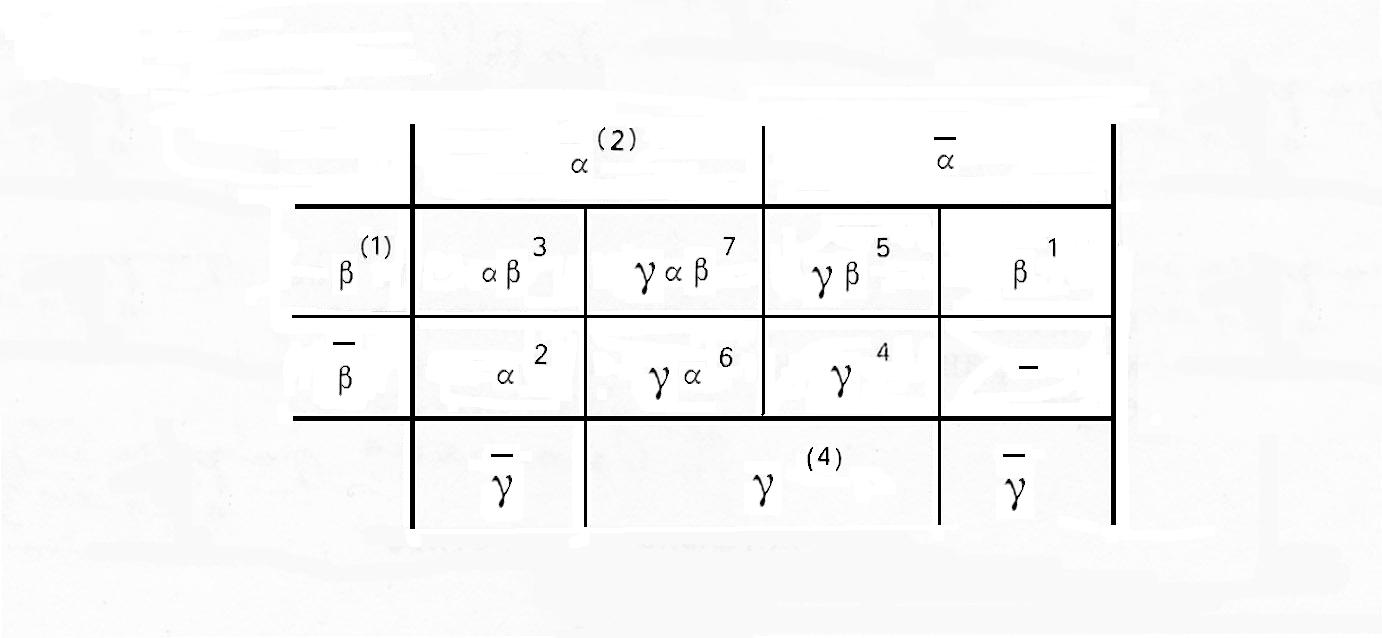

The expressive potentials of all the seven classes of archaic singing as compared with one another are shown, by means of quantitative indices, in the table 1, composed in accordance with the method of the so-called small Weitsch square, with the potentialities of the β-class taken to be a standard of measurement.

Table 1

1.6. There is no strict line between archaic melody-making and what is known as higher developed forms of singing. On the contrary, it was the evolution of primitive singing that resulted in the formation of tonal complexes with stable intertonal relations — in the crystallization of what is denoted here as t-principle of singing; this crystallization was attended by conquering the horizontal coordination of pitch-levels, with the intertonal relations being gradually fixed — instead of a mere juxtaposition of mobile melody tones — and what can be described as regular tone-system gradually emerging from the scarcely differentiated sound-substance. And notwithstanding the relative character of this stabilization of tones, which keep on varying within fairly wide zones, fluctuation is undergone not so much by separate tones as by their aggregation — the tone-system of a tune as a whole (see Ex. 84 and 85).

1.7. The formation of t-complexes results in qualitative mutations in tone-structures. Their expressive resources are appreciably increasing, for the discreteness is getting over the continuity. At the same time the primeval principles of intonation, which have been dealt with above, do not disappear — they merely recede. Their influence — from now on subconscious, as it were, — is limited and, though occasionally — and surprisingly — strong enough, hard to unravel. Anyway, a special emphasis on the juxtaposition of phrases showing a high contrast in pitch can be considered, in the context of a tune based on the norms of developed tonality, to be loaded with residual α-factors; wide-compass descending idioms (notably those with vocalized syllables and glissandos), to be remnants of the β-intonation; the phenomenon of varying degrees, to be a sequel of the γ-principle.

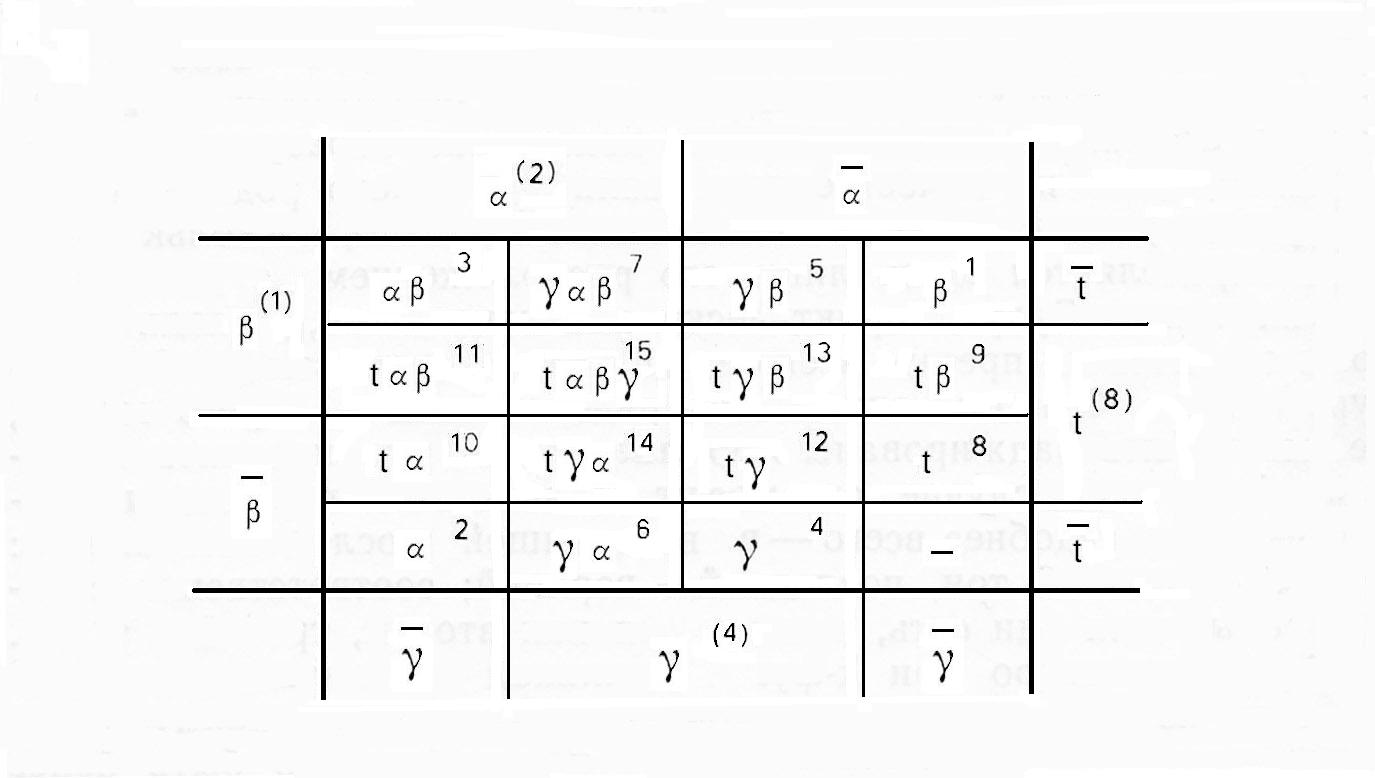

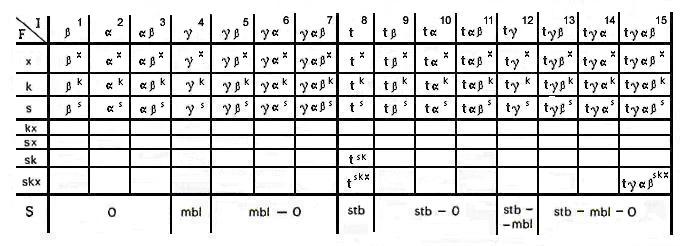

1.8. The general hierarchy of all possible types of the pitch organization of tunes (they are fifteen in number, and all of them are being used in practice) can be constructed in the form of the so-called large Weitsch square (see the table 2), with the expressive resources of β being chosen as the conventional unit (a standard of measurement), those of α and γ amounting to the doubled and, respectively, the quadrupled unit, and those of t being regarded as running to the redoubled γ-index and, consequently, excelling the total of the potentialities of α, β and γ. To sum up, the higher the rank of the principle ruling the organization of a tune turns out to be — and the greater the number of the principles participating in that organization, — the richer and pithier is, as a rule, the tune, that is to say, the greater its expressiveness.

Table 2

2.0. The problem of functional differentiation of melody tones, dependent not only on their pitch characteristics but also on rhythmical and structural factors, is much more complicated, and can be broached here merely by way of preliminary discussion.

Two general principles of functional organization of tunes appear to be operative: (1) coordination of melody tones, all of which are equipollent (k-principle), and (2) subordination of tones, hierarchically unequal in their import (s-principle).

In early folklore, these principles manifest themselves mainly in γ-melodies and, partly, in α-tunes. In t-type melodies they get delimited even more definitely so we can easily discriminate between two cardinal channels of t-melodies: to use nonce-coinages, 'coordinatonicism' and 'subordinatonicism'.

2.1. In the context of coordination there is no central element, no predominant tone, no 'tonic'. Here the quantity of degrees used in a tune is essential — not their qualitative differentiation. Functions of that kind (k-functions) can be called nominative functions, since the part a tone plays in a melodic whole is determined but by its place in the scale. Virtually equal in 'authority', the tones of a melody interrelate merely in pitch as such, their functions are uniform, and cannot be put in ranks save in their scalar order (most reasonably, in ascending sequence — tone 1, tone 2 and so on).

2.2. As no tone of a k-tune has an advantage over the others, the tones participating in such a tune are distributed within the melodic whole more or less evenly as regards the total duration of any one of them and the quantity of syllables sung on the corresponding pitch-level as well as the metrical, rhythmic, melo-syntactic and architectonic context (inter alia, the frequency of a given tone occurring on accented and semi-accented beats, in initial and terminal points of melodic syntagmas, etc.). That is to say, the employment of different tones of a tune functionally organized on the principle of coordination is well-balanced in every respect, of which one can judge from uncomplicated statistics (with due regard for the well-known prominence of the highest sounds and the preponderance of the deep ones as well as the importance of cadential tones)3.

It is only natural that the functional equilibrium is easier to attain where use is made of a limited number of tones (see Ex. 60), yet it also happens to be the case in more comprehensive tunes (see Ex. 52).

2.3. The k-principle cannot be fully realized unless the intervals between the tones of the scale are either equal (and sufficiently wide) — as in the whole-tone scale and in some other scales made up of equidistant constituents (see Ex. 57 and 68) — or evenly contracting in the direction of ascent, which is the case in the framework of what can be described as 'proportional' scales (see Ex. 70); in the latter, which incidentally show similarity to the harmonic (overtone) series, the intertonal distances contract as the efforts of the vocal cords increase. To generalize: the pitch dimensions of early folk tunes being unfixed, the principle of coordination is apt to even up the scales in use.

In the end, the evolution of 'coordinatonicism', submitted to the influence on the part of acoustics and psychology of sound, tends to give rise to anhemitonic systems, such as the generally known tonal pentatonic scale.

2.4. The formative principle of subordination, which calls into being numerous functionally differentiated, hierarchically organized systems (with s-functions), presupposes direct or indirect (mediate) subjection of all the tones participating in a tune to one or several apparent centres. An indication of such an organization, accessible to our musical instinct, is the impression that certain tones tend towards the others, which can be statistically substantiated in data showing how these tones are distributed in time and space (see Ex. 24 and 81). The emergence — and the adequate realization (apprehension) — of the phenomena of 'leading notes' and, what is no less important, of quartal and quintal patterns, with their acoustic cohesion, brings about a juxtaposition of wide and narrow intervals within the scales, no longer uniform in structure, and, finally, an ever-growing differentiation of whole tones and semitones. Typical representatives of the s-functional systems are different forms of diatonicism.

2.5. In this connection, we cannot but revise the generally adopted interpretation of diatonicism as a result of evolution of pentatonic formations, with the anhemitonic pentatonic scale being considered an under-developed form of diatonicism: as a matter of fact, both have self-dependently evolved from the common early folk sources, and the principles underlying their functional structure are essentially different. The two systems uncompromisingly diverge as .regards the spheres of expressivity pertinent to either of them; they also diverge in respect of the paths they follow in the history of means of musical expression. In particular, diatonicism is capable of intensive development, whereas the pentatonic scalar system tends to self-conservation and rigidity.

The above implies, of course, no argumentation in terms of appraisal. Diatonicism does not secure developments in the matter of tonality against what can be referred to as 'blind alleys'. On the other band, the pentatonic resources are far from being exhausted. 'Furthermore, pentatonic and diatonic modes prove to be able to fruitfully interact in that they bring into existence viable hybrids, as is the case where the zone of pentatonic songs and that of diatonic singing overlap, e. g., in the folklore of some of the peoples of the Volga area and the Urals; such hybrid cultures are the tradition of Bashkir 'drawn-out' songs and — an even more striking example — the distinctive vocal and instrumental music of the Kalmyk.

For all that, pentatonic and diatonic modes are divergent in nature. They differ not so much in quantity of degrees in the scale (five v. seven) as in principles of functional organization, which substantially contravene (coordination of 'hardware' degrees, more or less equal in import, as opposed to subordination of more flexible melody tones to a common centre).

2.6. The contravention of the two functional principles does not exclude their interaction. Already in early folk practice — alongside of coordination and subordination — there are intermediate forms where both principles make themselves felt. Often enough, e. g., certain tones are concurrently subordinated to two, or a greater number of, mutually coordinated equipollent 'stanchions', which gives us much ground to regard such polycentric, functionally variable formations as manifestations of sk-functions.

2.7. The centralizing (subordinative) and decentralizing (coordinative) forces do not cover all possible factors of functional organization of tunes. Among the other formatives are structural dynamics, e. g., the triad 'impulse—motion—termination' (as put forward by Boris V. Asafyev), and the norms of what is known as 'melody of speech', particularly as regards folk-songs sung in tonal languages (those with semantic intonation, such as Vietnamese); incidentally, the interrelation between musical intonation and verbal inflection deserves thorough research.

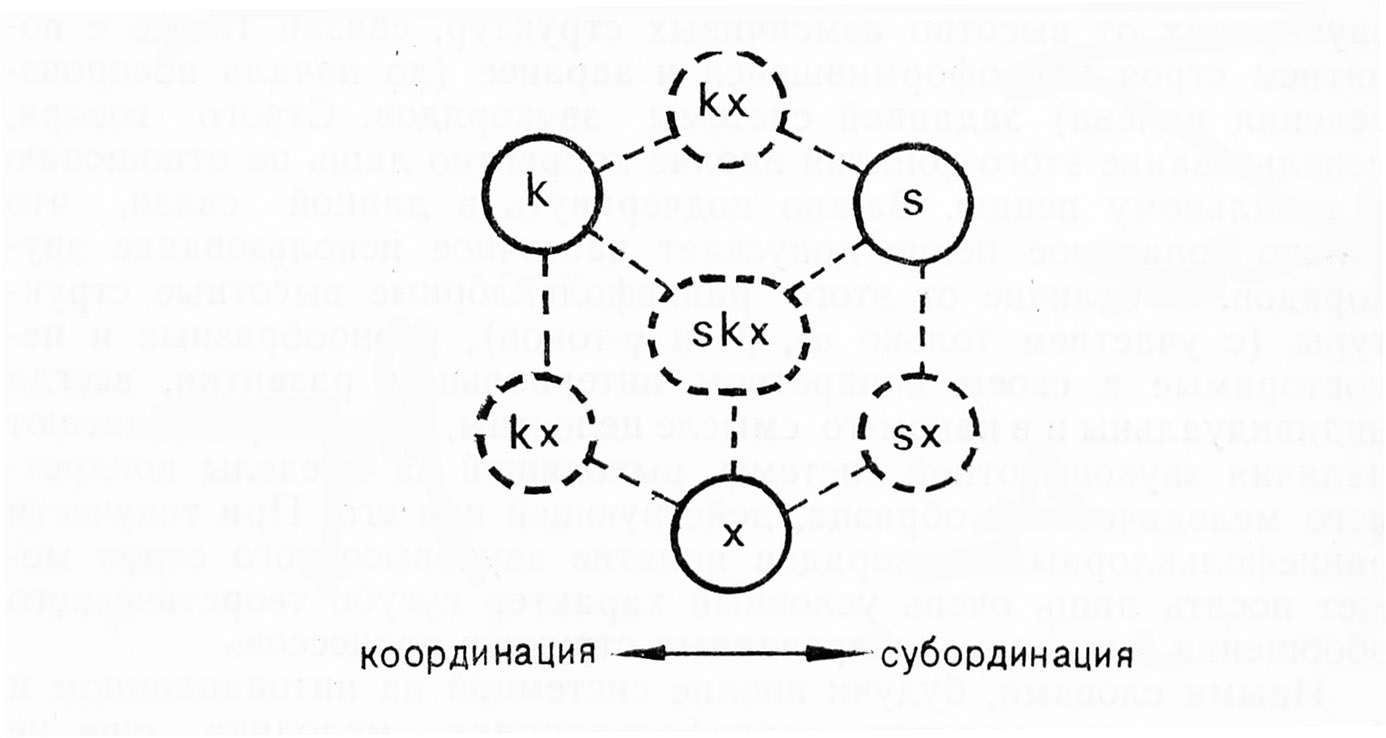

Therefore, there must be, besides k and s, at least one additional relevant principle (of a different nature) — x, so the overall typology of functional principles of intonation is bound to take on the appearance of a three-component scheme:

Diagram 2

3.0. The matter of scales is the 'best-built-up area' in our field of knowledge. Yet the process of scales taking shape remains somewhat vague, and the problem of systematization of such not-yet-fixed formations is still far from being worked out.

3.1. As to the scalar aspect of singing, there can be, generally speaking, three cases: no scales (non-scalar singing, 'zero' case — 0), mobile scales (mbl) and stable scales (stb). Cases 0 and mbl are incidental to the early folk practice; case stb is characteristic of the mature tonal systems.

The three possibilities as referred to above being able to be realized not only apart but also jointly (in one and the same folk-tune), a comprehensive classification of scalar forms of melody-making ought to encompass seven distinguishable varieties (see table 3 in 4.1.).

3.2. There is no strict line between mbl and stb — estimation is to a considerable degree conditioned by cultural traditions. (In this respect, cultures dominated by solo singing differ much from those highly influenced by instrumental music-making.)

The main criterion is the width of the zone within which sounds of different pitch are integrated into an indissoluble melody tone; this measure varies from culture to culture. With the average width of the zone normative for a given culture having been empirically calculated, we can differentiate between fortuitous fluctuations and meaningful gradations (of which the singer is aware).

3.3. No less important is the category of tone-system, which implies the existence of a crystallized (pre-fixed) complex of scales. Strictly speaking, this notion is unconditionally applicable but to the context of mature tonality, which, in contrast with the primeval forms of operating different pitch-levels (α, β and γ only), admits of making use of a part of a definite scale. In primitive singing, there is no scalar system beyond the sound-material employed in a particular piece of music so the concept of tone-system, if adhibited with reference to the practice of early folk singing (with its irregular 'structures as processes'), cannot but bear a somewhat speculative character.

To put it differently, although the substance of archaic melopoeia is system-bound on the plane of intonation as well as in functional terms, it lacks this quality in its scalar physiognomy.

3.4. For all that, it is analysis in terms of scalar structure that appears to be the most promising scientific approach to such melodies, for it leaves room for exact measurement and evaluation, and, consequently, enables us to formalize the methodology of research by means of introducing numerical criteria admitting of algorithmization and computerization. But a methodology of that kind presupposes unambiguous acceptances of such notions as tune, tone, zone and fluctuation in pitch.

Given that tune is regarded as a stereotype (in terms of pitch and structure) underlying the periodic organization of a definite melody line; melody tone, as a complex of sounds which are kindred in pitch and at one in function (with respect to the tune as a whole); zone, as the range of frequencies embraced by one melody tone; and fluctuation, as accidental, haphazard deviation of the pitch of a tone from its average level, — then the absence of scales (0) will be characterized by what may be described as adventitious distribution of pitch-levels and their extra-zonal fluctuation (fluctuation of a tone beyond the scope of its conceivable zone); mobility of scales (mbl), by what turns out to be fluctuation of the tone system as a whole, with extra-zonal modifications (smooth and orderly in direction) of one, several or all melody tones taking place as soon as the tune is repeated; and stability of scales (stb), by exclusively intra-zonal fluctuation of melody tones in any instance of the tune being repeated, which does not exclude removability of the tone-system as a whole.

3.5. The process of formation of scales is affected by functional actors, as well as by some other formatives of intonation. Hence, the scalar analysis furthers the differentiation of tunes on the basis of functional and linear criteria. There is evidence for interdependence of functional organization of tunes and the surface structure of their scales, expressible in terms of intervals (see 2.3 and 12.4 above)4.

In categorizing a given tune as an instance of one of the three types of early folk intonation (α, β, or γ) on the basis of its scalar material, it is reasonable to take account of its ambitus as correlated, on the one hand, with the quantity of registers made use of as discriminative tone colours and, on the other hand, with the width of intra-tonal zones. Then, the α-type will be testified by gaps in pitch coinciding with those in timbre (besides the impossibility to identify individual tones owing to their extra-zonal fluctuation); the β-type, by permanent extra-zonal mutability of the pitch quality throughout the time of one tone (syllable) being sounded; the γ-type, by consecutive extra-zonal transformations of tones every time the tune recurs (besides the localization of a number of tones within one and the same register identifiable with a definite tone colour). As to the scalar criterion of the t-type intonation, it naturally does not differ from the criterion of stability of scales.

4.0. Last, it is necessary to touch on the problem of interrelation as between different planes of the pitch organization of melody, viz. in respect of (1) place (scalar aspect), (2) role (functional aspect) and (3) sense (semantic aspect of intonation). Though each of the three planes shows qualities of an autonomous system, they constitute, considered together, an organic whole built hierarchically so that the second — or the third — plane absorbs, modifies and reinforces the mechanisms pertinent to the first one — or, respectively, to the two previous planes. The simplest of the three aspects, easiest to cope with analytically, is the scalar physiognomy of tunes. On the functional plane, psycho-physiological factors are superimposed on the intervallic framework, with meaningful differences in penderosity resulting from the context in which individual tones of the scale are used within a definite tune. And, in the final analysis, the semantic plane of organization of pitch-levels encompasses all possible manifestations of interaction of the tones constituting a melodic whole — not only within the limits of one or another tune but also from a much wider angle, that is to say, in the socio-cultural context.

4.1. The above can be generalized in an all-inclusive table reflecting the typology of both primitive singing and mature melodization, with the tables referred to in 1.5 and 1.8 being, so to speak, built in. All possible principles of intonation are symbolized in the 15-division row of the table 3. Likewise, the functional axis can be complemented (by adding four combinations of k, s and x — kx, sx, sk and skx) to form a 7-division row.

Table 3

4.2. It is noteworthy that the purport of α, β and γ as participating in the right part of the table differs from the identical concepts as figuring in its left part, where the corresponding principles are not yet supposed to be subordinated to the dominance of mature tonality. In melodies controlled by the t-principle, conceivable manifestations of α, β and γ are residual in nature so that, e. g., the tγαβskx combination, imaginable in the case of our table displaying all the possibilities it admits of according to its very scheme, would stand for none but crystallized tonality, albeit impregnated with variable tones (mutable degrees of the scale), contrasting registers, glissandos etc. as well as with verbally conditioned functions and — under the aegis of stability — mobile and non-scalar sections (which can be expressed by means of the formula stb – mbl - 0).

Thus, the table 3 covers, in first approximation, the whole range of functional and inflectional potentialities of sound communication, both verbal and musical. Any specific melodic culture can be correspondingly classified so as to be represented in a definite cell (definite cells) of the table.

4.3. The methodology of classification underlying that table can also be applied to some other aspects of musical speech, such as rhythm and metre, i. e. organization of tunes in terms of time (for all its irreversibility), or the interrelation of verse and tune. In the flow of sounds, initially amorphous and undifferentiated, comparatively long and short sounds emerge, though with no definite proportionality, or approximately equal (in duration) sounds alternate with rests (by analogy with α and, respectively, β).

Diagram 3

4.4. Back on the plane of pitch-levels, the question arises whether the classifications suggested are consistent with the real state of affairs as regards the organization of the sound continuum in early folk singing.

The answer can be arrived at but on the basis of utilization of the methods under consideration by means of computerization of analogous models. For the time being, we can summarize our arguments in a hypothetical chart (see Diagram 3) of the evolution of thinking in terms of pitch from primordial (embryonic) mobile forms (see the left part of the diagram) towards the stabilized systems of pentatonic and diatonic modes (presented in its right-hand part). The latter appear to have developed from the γ-principle of early melodization in two strictly differentiated streams of tonal organization (k and s).

Early types of intonation in singing have been described here in relation to qualitatively different states of the melodic tone — with regard to the absolute and relative parameters and the extent of 'articulatedness' and semantic import of its pitch. Notations of early folk tunes are based on different methods of modeling archaic melodies in graphics, and, accordingly, have to be read into in different ways.

English version: V. Yerokhin

1 This statement may appear objectionable: instrumental music-making has acoustic and material sources of its own, and can have followed a fairly self-dependent road. However, if we take into account that in the final analysis playing an instrument is, in a sense, 'singing' through the medium of the instrument, and that any sound evokes the so-called idiomotive response of the vocal cords, we shall see that there is every reason to admit the priority of the voice.

2 Musical examples in this book make use of the thirty-six-degree equal temperament, in which the semitone is divided into three parts by means of inserting two complementary accidentals:  (for micro-sharpening — by 1/3 of the semitone) and

(for micro-sharpening — by 1/3 of the semitone) and  (for micro-flattening); in letter names of notes (with the syllables -is for common sharps and -es for flats (in German nomenclature), additional syllables are employed, viz. -it (for micro-sharpening) and -et (for micro-flattening).

(for micro-flattening); in letter names of notes (with the syllables -is for common sharps and -es for flats (in German nomenclature), additional syllables are employed, viz. -it (for micro-sharpening) and -et (for micro-flattening).

3 For the 'tabular statistical method' of analysing melodies in terms of functions of their constituents, see Alekseyev, E., Problemy formirovaniya lada ('A Study of the Development of Modality'), Moscow, 1976, p. 153-161.

4 As stated above, the main criterion of functional differentiation of tones is the nature of their distribution in the sound-material in use to be found out by means of statistics: k-functions are evidenced by equal distances between the tones; s-functions, by unequal ones.

Глава 1 Глава 2 Глава 3 Глава 4 Глава 5 Глава 6 Глава 7 Послесловие

Литература Summaries Приложения